Radiohead – 15Step (2007)

Art should provoke. Else, we have only politics and pickup trucks.

Popular music has had an uneasy relationship among its contributors for as long as we folks have clapped. Largely an oral tradition, the music of the masses has only gained real stickiness from the time of the phonograph onward. Before that, it had barely a century of limited-distribution ‘sheet music’ and whatever folkloric subversions coursed through the veins of carefully-notated profane ‘classical music’. In the western world, our musical sensibilities have grown up along two competing heritages: learned, crafted, well-financed musical models of Church and Court; and spontaneous, crowd-sourced, unlicensed slams of you’n’me.

Naturally, the two have always criss-crossed. Fuckyou folktunes were showing up in Gregorian Chant over a thousand years ago, and if it weren’t for the musical elite, we wouldn’t have the accordion today. Okay, bad example. Point is, because pop and classical musics have always suffered a can’t-live-with-em, can’t-live-without-em codependence, there are always those whose ecumenical ambitions try not only to exert or absorb influences of each, but even to deliver both in a single oeuvre. That’s how Bela Bartok happened. Okay, bad example.

From the pop/folk music side, the immigration of classical elements has been much harder to trace, largely because the composers composing the heavy stuff for State Jubilees and Special Sunday Masses have often been the very same sots barking out obscene limericks to jaunty melodies in local freehouses and private salons.

[ed. I can tell you with authority that the sorriest sight you’ll ever see is a half-dozen musicology students on their fifth litre of beer singing along with Billy Joel on a Friday night in a stanky bar across the street from the dusty, wood-paneled music library]

Indeed, the two streams of music and their inspirations have never actually been separate. Only their contexts have set them apart. I never, for example, needed a sonata-form movement augmented by a full orchestra to lullaby my daughter to sleep, nor am I missing a funky three-note guitar hook to praise my higher power in the company of fellow worshippers.

Largely, rock music has been all about a few self-instrumented musicians writing their own catchy tunes, singing about how horny or heartbroken they are, and getting other insecure young people to sing along with it because they’re just as horny or heartbroken (and they can’t play barchords to help express it). It’s supposed to be free, it’s supposed to be raw and the ‘elite’ – whoever they are – are unwelcome. Counter-music for counter-culture.

But everyone gets ambitious, and subversive rock musicians are no exception. The so-called Art Rock movement, conceived in English recording studios in the 1960s and midwived by the psychedelia culture that followed, attempted to elevate the language of the youth to the big-people table. Songs got longer, not from lengthy solos and jam-sessions, but by sophisticated composition forms that housed multiple melodic themes and progressions. Harmonies flourished beyond their three-chord chrysalis and tonalities drifted wayward from one key to another, and then another. Orchestral arrangements thickened the soup not just with a gush of single-line string ensembles but with full orchestral textures that contributed to the song’s development. Lyrical subjects called on history, literature, philosophy, science and fantasy, not just hormones and social reflux. And this musical reach now demanded new levels of instrumental virtuosity that had popped up only rarely in earlier pop music renditions. Those demands revolutionized playing technique across all rock-band instruments and also laid out the requirements for emerging technologies to create the sounds that had only existed in songwriters’ and producers’ heads.

That rare air has wafted in and out of vogue over the past 60 years. A bevy of pioneering art- (or ‘progressive-‘ or just ‘prog-‘) rock bands were deities in the 70s, cartoon characters in the 80s and godfathers in the 90s and beyond. You could set your watch to the Grassroots and the Baroque trading places as the New Cool.

Once in a while an artist or group of artists comes along and just transcends the whole fight. The Beatles, then King Crimson and later Yes and Genesis pushed the first wave. Their music exhilarated many and also made critics and mainstream listeners twitchy at the very notion of rock music becoming une langue soutenue. Whole listener segments were put off by a subgenre that defined itself as the anti-style of an anti-style. On the other hand, these large-media prog artists gifted fledgling FM radio with an AOR roster that minimized the on-air talent spend, record companies had their full-album brands, and recording artists had a creative framework that sneered at the need for hit singles. Be creatively inspired and get paid too? Winning.

But in the end, we masses always win, usually in spite of ourselves. Flavours of the month – punk rock, new wave, hair metal, synth pop, hip hop, goth and later grunge – conspired to shelve art rock and its proponents in fairly short order. The loathsome bloat of eight-minute songs and their pretentious themes became a laughingstock. It’s not that their creative spirit went away; that’s never been the case. But if only sophisticated expression could fit into more consumable sizes and still speak to the sturm und drang with which young listeners had put art rock to the curb. If only…

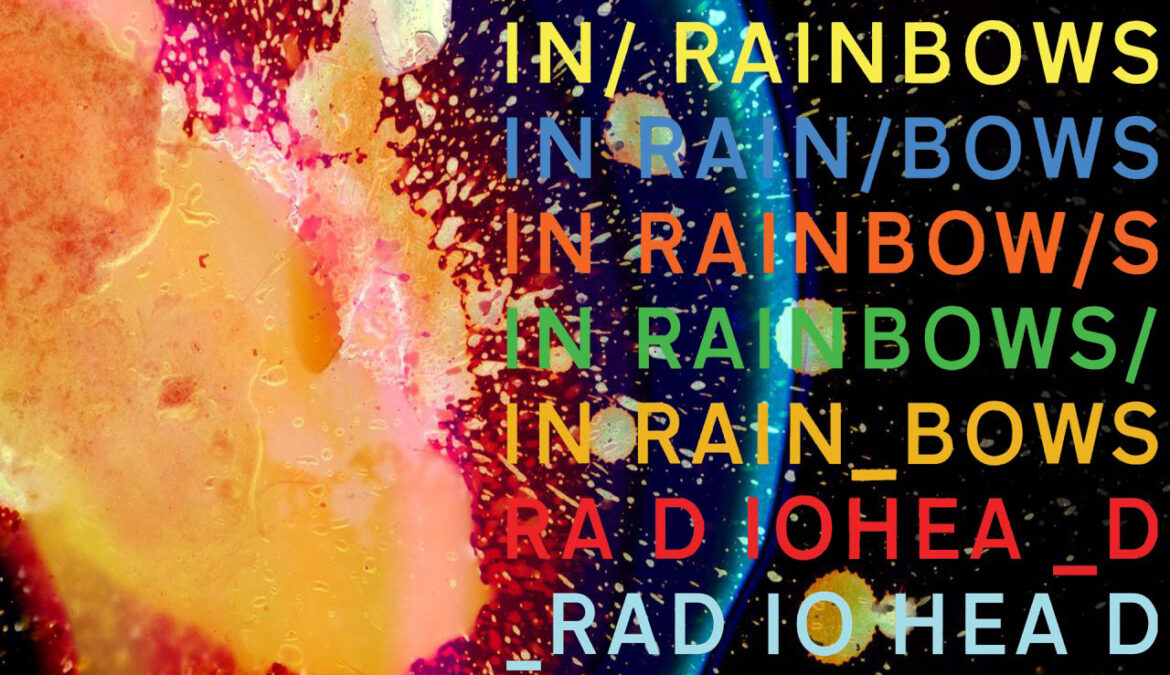

It’s hard to think of a band in the past 30 years that has been more musically creative and artistically provocative than Radiohead. Fairly user-friendly out of the chute, Thom Yorke & Co. opened up a 48-ounce can of whoop-ass on the music world with 1997’s OK Computer – arguably one of the ten most critically-acclaimed anthologies in recorded music history – and hasn’t taken its foot off the creative accelerator since. Each of Radiohead’s nine studio albums, fairly equally spaced, measures a stark leap forward from its earlier work. No parameter was off limits, no musical assumption immutable. Familiar verse-chorus structures were out the window and over the fence. Instrumental virtuosity, though resident, was nowhere on offer. Power-chords were the stuff of caricature. Love songs were sparse. Tonality was functional, but only when that was convenient. The message was cardinal, and whatever musical devices it took to deliver it were Radiohead’s stock-and-trade. No rules.

With that, I’ve basically killed my own intro to 15Step. That the song is in a manic, up-in-your-kitchen 5/4 meter throughout, is unremarkable. This kind of unapologetic sharp edge is at the very least familiar to their followers, if still perfectly uncuddly. The song is unsettling, one where the musical interpretation can easily mismatch the lyric. The latter is a piece of frustrated self-reflection (“How come I end up where I started?”), repeated verbatim with a sense of musical irony. The coda (“Fifteen steps then a shear drop”) is cryptic. It might be a macabre reference to a guillotine, but it’s certainly no trite, cheeky nod to the song’s five-based meter; in the first place, the phrases are all grouped into four square bars, and in the second place, it’s just not Radiohead’s mode to be so pedestrian.

The form of the song sheds some light: AB1B2CB3A is most certainly not cast through a songwriter’s stencil. A palindrome rather than a verse-refrain progression, the formal story arc mirrors the “end up where I started” text, and the instrumental coda with its jarring key change echoes the puzzling “shear drop” image. Within that framework, the guitars play gentle, tuneful riffs, the bass comes and goes, and the voice and all instruments save for the drums and sampled claps come and go like optional meeting attendees. Only the rhythm is constant. And it’s in five.

So what is this song – the whole song, not just the lyric – actually about? Well, there’s no official statement on that. Fan discussion forums pose that very question and settle on different answers, many of them thoughtful and compelling. Musicologist James Doheny has published an ambitious work on the subject of the band’s songs and their backgrounds.

Radiohead didn’t write 15Step to get us singing it. And clearly, they didn’t want anyone clapping along with it. They created this song to get us thinking about it and talking about it. That’s one of the many reasons that this band is very, very challenging to listen to.

They’re artists first. They’re here to provoke.