David Crosby – Find a Heart (2014)

Mixing post themes here, and breaking a policy rule to do it (the whole song needs to be in five/seven, nahnahnah bitchbitchbitch…)

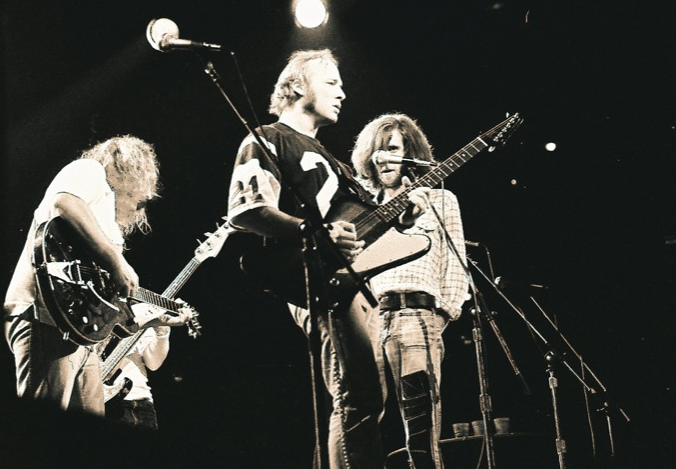

Great musicians can’t hide behind their music. It exposes them every single time. Sometimes it’s joyful, sometimes it’s terrifying. But it’s always beautiful, no exception. I’ve riffed on that at length.

The SoE is this: I discovered David Crosby‘s Croz album through Lee Sklar‘s YouTube post, downloaded the song, then two more, then the whole album, and like the heroin addict that was The Master Himself, kept chasing the musical high of that first song play. Only unlike the poppy-based opiate, this one rewarded me every time out. Then I checked out the rest of his solo oeuvre. His work with The Byrds and CSN(Y) was already know to me, but his own stuff less so. Then I watched the 2019 bio-doc David Crosby: Remember My Name.

I should have stopped with my investigation of his solo discog. There I discovered a riches of impossibly beautiful music, beautifully crafted, beautifully sung, beautifully played. I made the mistake of listening to it on my iPhone in a fit of appetite, lying in bed at 01:00. I couldn’t sleep the rest of the night, and my alarm woke me at 07:15, scant an hour after quiet slumber finally reached the unquiet sleeper.

But some nights later I watched the biopic. It was a balanced, informative expose on a life lived with all its tribulations. Crosby is The Voice, narration is thin, and only a few of the interviewer’s questions are heard off-mic and off-camera. But they weren’t soft tosses and the subject of the movie wasn’t always comfortable (or sincere, IMHO) answering them. And in the last 20 minutes Crosby’s world of broken toys is lain out for us. His lifelong friendships with Graham Nash, Neil Young, Roger McGuinn and Stephen Stills were now, in Crosby’s own words, irretrievably lost. Nash, for one, corroborated that. The others were not interviewed. When asked why he, Crosby, didn’t just show up on Neil’s doorstep to try to reconcile, Croz stared blankly for a desperate two seconds before offering, lamely, “I don’t know where his doorstep is”. In the final minutes of the film, wife Jan, supposing her husband’s end is near, tells through tears and cracking voice that she will not be able to continue without him. What a sad, empty twilight for an incredibly creative and eventful life, I thought. Croz, wellnigh an octogenarian, might be smiling back on his wild ride with gratitude in his heart and the pride of a musical legacy that will outlive him by centuries. But he just can’t seem to find that space in the course of pedestrian interaction. I never, ever cry when I’m sad, but I was choking on this ending (again, at around 02:00; I’ll never learn).

Crosby’s solo career has been in hyperdrive in recent years. Having only released three full-length solo albums prior to 2014, he has issued foursuch since, with another release imminent as of this posting. His most prolific, and at least under his own banner, his most creative period began at the youthful age of 73. Curiously, it has happened at exactly the same time that his most vital musical and personal relationships have dissolved.

And to listen to this latter-day collection of songs, there doesn’t seem to be a trace – musically, anyway – of anything missing in his spiritual world. There is melancholy, yes, but it’s balanced with songs of serenity and purpose and even joy. There is no creative metal fatigue. The songs of Croz fuse his rotating mastery of jazz, folk, blues and pop. Some songs are more singable than others, but when the hell has usability ever been the measure of art? Great music should provoke and challenge listeners, not just accompany ho-hum sex. Crosby’s recent work is no box o’ cupcakes.

Most important, even where he’s completely full of shit in his movie, Crosby doesn’t hide in his songs. They are the Great Reveal.

Find a Heart is a stunner. It finishes off a tremendous collection of now-narrative, now-confessional, always adventurous pieces with a sequence of verses, harmonies, textures and rhythms as rich as anything he’s ever recorded. It was co-written, -performed and -produced with his son James Raymond and cut with musicians young and old – Lee Sklar plays bass here and Mark Knopfler makes a cameo on the album’s opening track.

Not to commit an ageist major foul here, but musicians in the twilight of their careers don’t tend to push the envelope too far on listenability. Experimentalism is a young gun’s game, and that includes musical devices like, say, setting important passages of a song in weird meters, like, say, 5/8. Unless, of course, you know what you’re doing and you can deploy those tricks in a very user-friendly way.

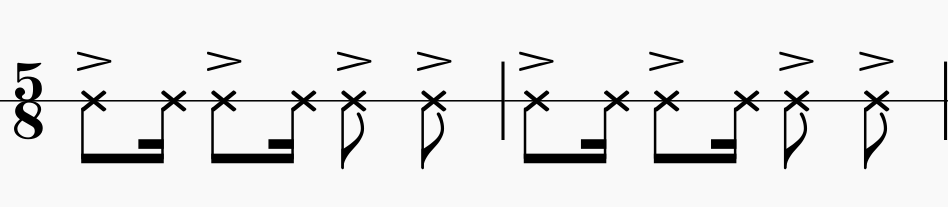

The post-chorus instrumental bridges at 00:52, 01:51 and 03:32 switch smoothly to 5/8, following sung verses set in a groovy 6/8. It’s a deft move. This otherwise tripsy five-beat time signature earns its catchiness two ways, both carried in the accompanying guitar and keyboard parts. You can interpret the rhythm two ways. First, as a doubling of the triplet 6/8 tempo followed by an emphatic one-two punch of eighth-notes, making a nice two-triples and two doubles (where the two triples carries over from the 6/8 time sig of the verse):

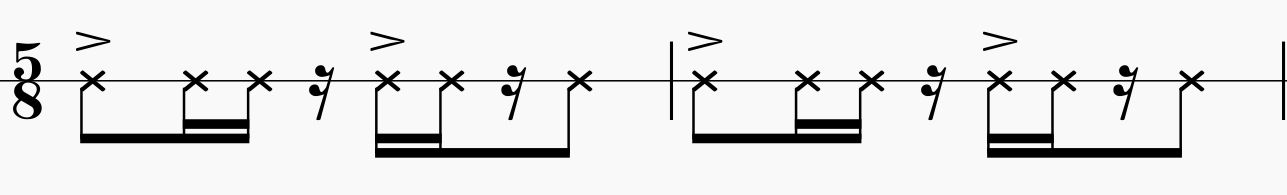

Or it can be heard as a morse-code-ish palindrome of long-short-short, short-short-long with a half-beat breath:

Either way, this passage absolutely dances, so much so in fact, that when the song returns to a normally-rollicking 6/8 it sounds almost as wooden as that ship on the water (sorry). Crosby’s Five is now a drug that we chase for the rest of the song. Sound familiar?

I mentioned the offset between texted verses in 6/8 and instrumental interludes in 5/8. That’s no accident. Five may have its dance applications, but it’s a bitch to set metric text to. Crosby’s first band, the Byrds, sang from the Book of Ecclesiastes that to everything there is a season (“a time to plant, a time to reap…“). In the current song, there is a time to sing and a time to play.

But after a stark breakdown (03:48) and crescendo, the dance continues (04:16), this time with textless voices added in lush harmony over top of the infectious five-step. The instruments are instrumenting and the voices are voicing with no worry about word-alignment. All the participants of the song are invited back in a joyous, ecumenical ending. It’s euphoric.

David Crosby the man on the street may not impress. If he doesn’t, just listen to the David Crosby the musician. That’s where the real person lives. Maybe that can serve to bridge the gap in his broken lifelong relationships. I swear, it’s not too late.