Peter Gabriel – Solsbury Hill (1977)

It had been nearly two years since the world had heard the voice of Peter Gabriel; typical today, but an eternity in the yearly albumtouralbumtour epoch that was the 1970s.

His prior album, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, was ostensibly Genesis‘ sixth studio album, but in matter of practice it was Gabriel’s first solo effort (he brainstormed the ‘concept’, wrote its attending story, and composed all of the lyrics and some of the music). It was a cold, empty, metallic, angry piece of business from start to finish, and elicits mixed opinions even among hardcore faithful to the present day. Indeed, Peter’s bandmates themselves remember both the work and their experience creating it with the same measured, post-traumatic stress that the music itself evokes.

So when Peter Gabriel 2.0 surfaced in February 1977 with his self-titled debut album, expectations were suspended in mid-air. None of his former bandmates was on the album. Robert Fripp (King Crimson) was engaged for European musical flavour and Bob Ezrin (Alice Cooper) was brought in as much for an American rock bent as for his production acumen. Classical art-rock melodrama was nowhere on offer, and gone too were the extramusical (and often nonsensical) stories, concepts and weighty historical and literary themes. This album would be far more personal, almost confessional; a clinic of self-actualization.

The album had a lead single. That alone was unusual territory for Gabriel, who threw a bit of shade at the music business in his ‘departure letter’ to fans two years earlier. He didn’t want his role to be defined by the industry to which he was indentured. Or something.

Solsbury Hill was a gentle, tuneful, very user-friendly foot forward for an artist who had been and would continue to be renowned for anything but. Its lyric told a story of letting go of safe structures and moving ahead with faith and confidence, even with a dollop of uncertainty. It was an inventory of Gabriel’s feelings and fears around venturing out on his own, leaving behind a successful, now-famous (if cash-strapped) band for a solo career that was late out of the gate and unguaranteed.

Did something need to reflect that unease? It certainly wasn’t going to be the imagery – that of a man at the top of a hill overlooking city lights with a wind blowing; the key wasn’t going to ruin the mood – an unmodulating B-major without so much as a single accidental was a jaunty bit of tonal wallpaper; the texture was no nightmare – the catchy acoustic guitar hook was as singable as the neatly phrased vocal melody cascading over it; and the tempo was an easy, walking-pace 100-ish on the metronome.

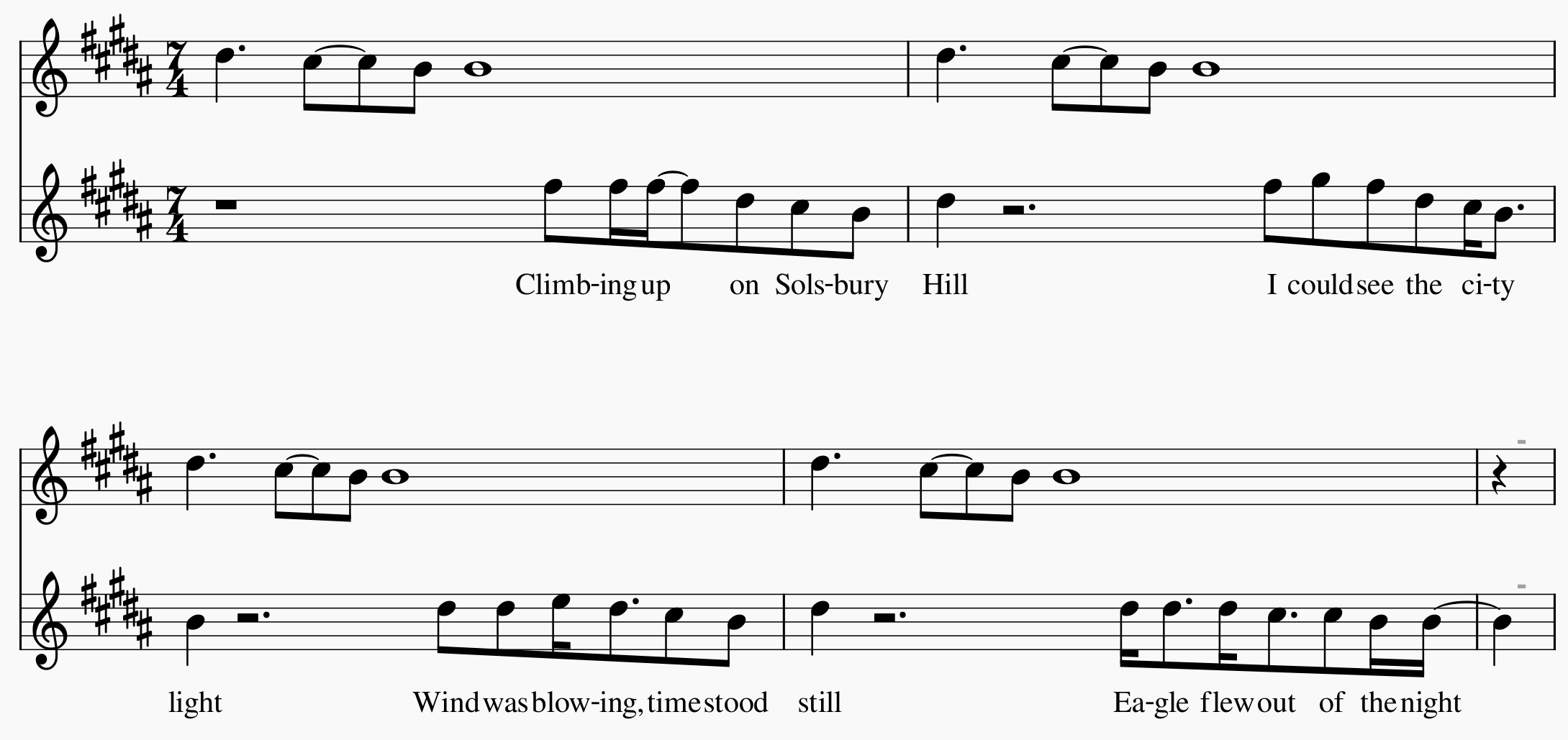

Few listeners ever noticed, mostly because of the song’s infectious hook and partly because of its even, unassuming quarter-note pulse, but the entire ditty is in a normally-maddening 7/4 rhythm. Only at the end of each refrain does a pair of 4/4 bars appear, and really it’s only to accommodate the scan of the lyric (“Grab your things, I’ve come to take you home”). The call-and-response between the orchestral motif and the voice divides the measure into a 4+3 pattern, but the offset is strictly melodic, and so the asymmetry is imperceptible:

A bit of word-tone here? Is he trying to give us a musical depiction of his new, uncertain, unsettled state? Maybe.

It’s a long-forgotten funfact that Peter Gabriel was a drummer before he was a singer or pianist. His innate affinity for rhythm is marbled throughout his entire creative output in some pretty dramatic and signature moments: the African-inspired textures and rhythms of Biko, Intruder, and Rhythm of the Heat, not to mention his founding of the itinerant global festival World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD).

But less obvious is his near-genius ability to marry the rhythms of text and music. It’s very rare that you will hear a word’s syllables wrongly emphasized in one of his songs. This is usually the bane of songwriting partnerships where one writes the words and another the music. Listen to Alanis Morrissette‘s Unsent (lyrics Alanis, music Glen Ballard) – the misaccentuation of words in the musical measure is beyond painful, it’s absolutely cringeworthy. Neverwillyouever hear that misdeed perpetrated in a Peter Gabriel song. He won’t compromise the musical meter; he won’t compromise the cadence of the text; and he won’t compromise lyrical meaning. He wants all of it and he’ll bloody get it. Every time.

Even if he needs to write his very first hit single in 7/4. Man, that’s fearless.