Okay, so yesterday we loaded the gun, and today we fire it.

Gun, you’re fired.

[it’s Amateur Night at the Chucklehut]

Let’s get back to our modes. Remember them? Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian. If you need an acronym to remember them, it’s IDPLMAL, which is actually pronounced “idplmal”.

In modern music, it’s largely two modes that are ever used – Ionian and Aeolian, more commonly known as Major and Minor. But what about those other modes… are they ever used? Are there examples of them in pop music recordings?

Indeed there are, and although their provenance is centuries-old classical and folk music, at least two of those modes – Lydian and Mixolydian – have hung around with us, largely thanks to blues and rock & roll.

First, let’s get the major-minor thing out of the way. Stairway to Heaven is in A-minor, Let it Be is in C-major. Box checked. Quite likely every song you’ve heard on the radio today is in one or the other of a major or minor key.

But every once in a while, a songwriter will slip a little exotica into your playlist.

Here’s one: The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia, originally recorded in 1972 by hacktress Vicki Lawrence (later covered by Tanya Tucker and then again by Reba McEntire) is the archetypal Dixie murder ballad. It has a compelling story set to a great lyric, and a great verse-chorus formula to tell it. The chorus is solidly in F-major, and the verse is in… what? It sounds and smells a lot like B-flat-minor. It isn’t. Listen to it; does anything stand out?

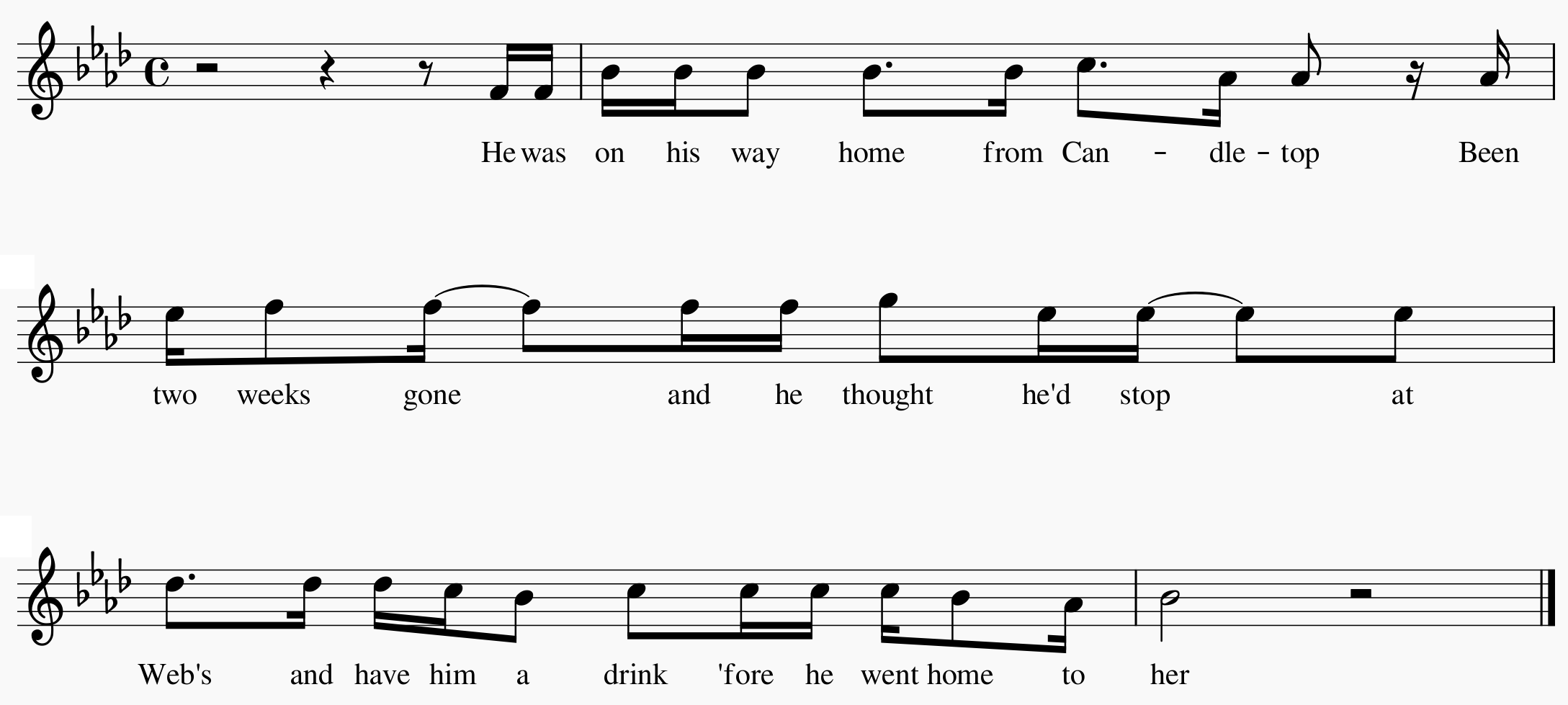

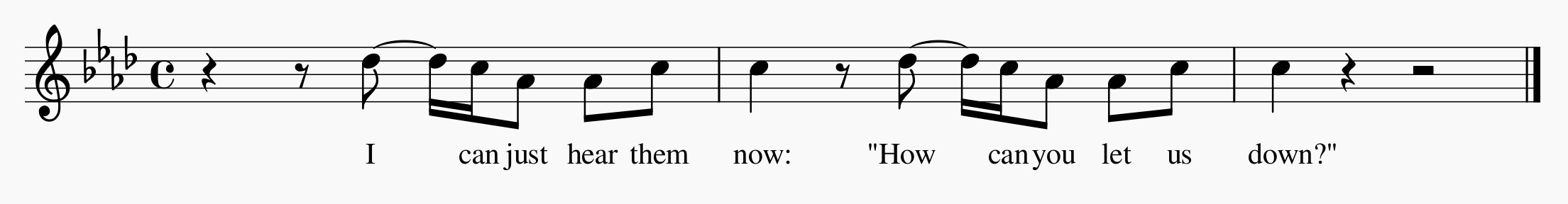

If you follow the pattern of the Aeolian (aka ‘minor’) mode, the sixth note of the scale is three wholetones up from the key’s B-flat root. That would be a G-flat in the key of B-flat-minor. But the melody doesn’t use G-flat, it uses G-natural, a semitone higher (on the word “thought”, below).

The key isn’t B-flat-minor; it’s B-flat-dorian. It’s a striking melody, unique and memorable. Simply, it makes the song, and I’d be so bold as to say that if that one single note had been a G-flat instead of a G-natural, Vicki Lawrence’s legacy would be naught but a foil to Tim Conway on the Carol Burnett Show.

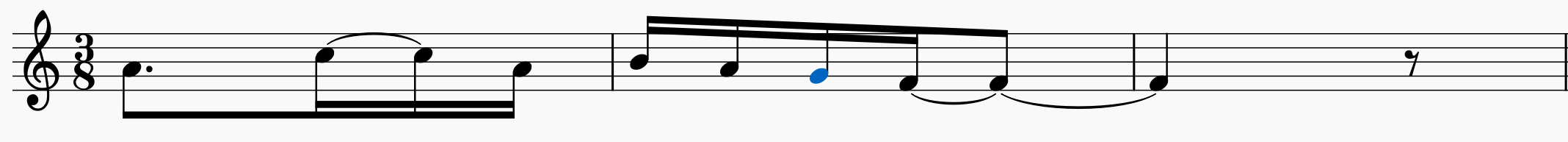

Here’s another: Runaway was the The Corrs‘ very first single from their very first album Talk on Corners. No ordinary toonsmiths, they. This impossibly talented family act marbled their Irish pride proudly through their music. Often it showed up in full-frontal offerings (Lough Erin Shore and Haste to the Wedding are just two of many fantastic ethnomusical paragons in their catalogue), but every here and there a little loonie was planted at centre ice to remind us that this wasn’t just another CD sale.

Sharon’s lovely violin hook at the beginning of the song and after each verse-chorus is the song’s signature. The key is rightly F-major, and the violin sticks dutifully to that key’s requisite B-flat fourth degree of the scale. But after the last chorus (at 3:28) the violin plays a B-natural instead of a B-flat, switching the key to a striking F-lydian. It’s positively spine-tingling.

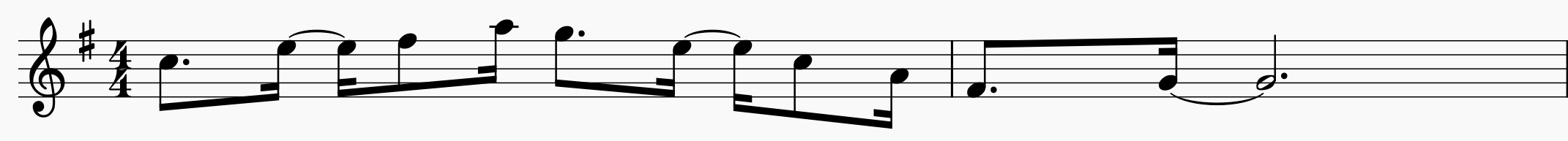

Need a more familiar example of the Lydian mode? The theme song of The Simpsons is in C-lydian (the F-sharp replaces the F-natural that the key of C-major would command):

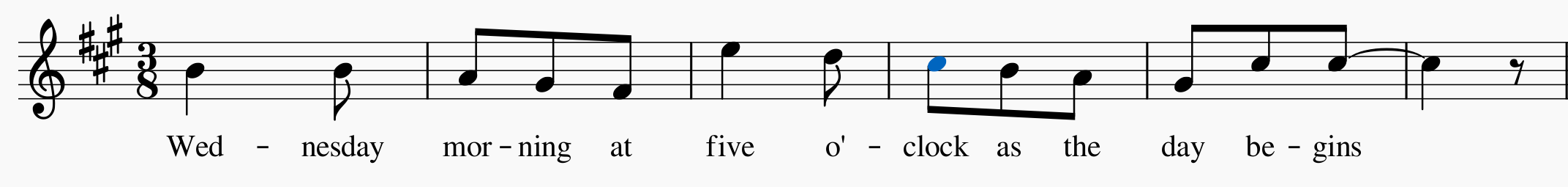

Wanna Mixolydian? I render unto you one piping-hot Mixolydian, then. Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band has been called the greatest rock and roll album of all time. Who am I to bicker? Truly, there’s something in it for everyone, and one song that stands out on the album is She’s Leaving Home; it’s a heart-rending story (inspired by real events) narrated in both the first and third person, and accompanied by no Beatle whatever. Only a small string orchestra weeps in sepia while a teenage girl leaves her parents’ home to pursue love and independence. The normally-sympathetic counterculture story is told from the devastated parents’ PoV, set against classic instrumentation and… a traditional folk-song mode.

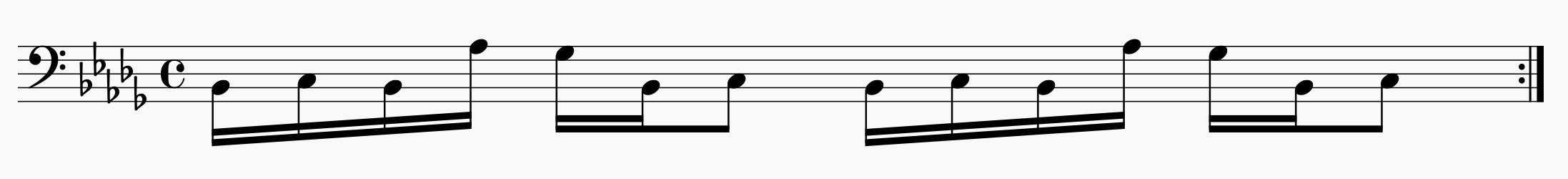

The D-natural on the “o” of “o’clock” displaces the D-sharp we’d have heard if the song were in E-major rather than E-mixolydian:

It lends a sad past tense to the story, one sensitively told by a pair of songwriters that must have caused many parents of the day no shortage of angst.

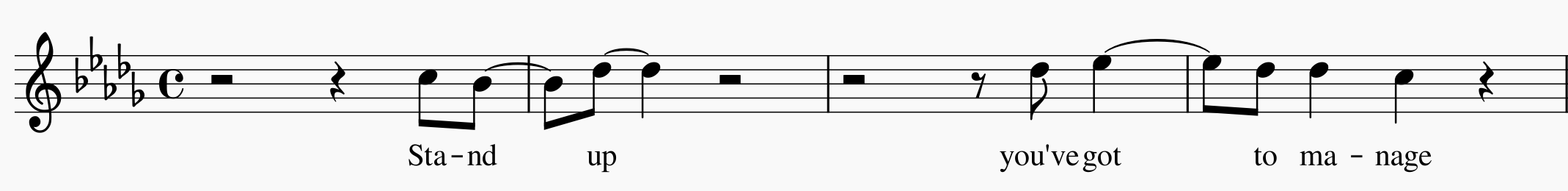

Next stop on the tour is the ol’ ST T T T ST T T (this is a test: which mode is that?). I won’t post the song again since I wrote it up here in the Tiny Moments series, but Kevin Parker‘s (aka Tame Impala) New Person, Same Old Mistakes uses the Phrygian mode very artfully. Notice the very first line of the song begins on the very note that defines the mode, namely the second note of the scale, here a D-flat for a song that’s in C-phrygian:

The brute repetition of this melodic line over and over again helps to polarize the C for a mode that can sometimes be difficult to pin down, as we’d often hear the C as the fifth of a minor mode. Parker knew exactly what he was doing in this song; the meandering between the C and D-flat tone-paints the tension in the lyric narrative between the new person and the same mistake. It’s a brilliant choice of musical devices.

There’s one left: Locrian, the Fallen One.

Really, the mode exists in name only. In nine years of music study, I don’t remember coming across a single musical work that uses it as a tonic key. I’ve reviewed the reasons why, but at the end of the day, our ear will never accept a ‘diminished’ chord (with a flat fifth, or ‘tritone’) as a home base. It wants – needs – to resolve to something more ‘stable’.

However, there is one song by Björk, Army of Me, that gives it a credible try. David Bennett has prepared and posted a fantastic video that examines her curious choice of tonality in critical detail, so I’ll only skim the surface here, but the essence of it is that the lowered fifth of the Locrian scale is established in the bass with a repeating ostinato

while the polarity toward the tonic C is set in the vocal melody in careful counterpoint (she avoids the G-flat):

Because the diminished chord is never actually played by any of the instruments, we never do suffer that unstable ‘crunch’ of the home key. Björk eventually has to cave in to a G-natural in the chorus, but by that point, we’ve heard the Locrian pattern enough that it’s established, however uneasily. It’s a tiny needle to thread.

I’m always impressed by the resourcefulness of songwriters and musical craftspeople who are unafraid of using some of the more crooked tools in the shed. Non-major/minor modes are dicey: because that binary is so baked into our listening DNA, it can be very disorienting for us to hear something elseward. It’s entirely possible that composers use the more exotic modes unconsciously – folk music from deep traditions in childhood can be indelible. Whatever their motivations, the richness of their flavour is undeniable, and can make for some remarkable musical moments.

Well, that concludes our two-day tour. If you’ve made it this far, GET A LIFE!

Just kidding. The Chucklehut never closes…