Coldplay – Clocks (2002)

Many songs start with a good hook, it’s just natural. An instrumentalist hears a nagging repetition in his head and just can’t function in society until he’s at least played it for someone, if not used it holus-bolus in a song.

It doesn’t happen often, though, that an entire composition grows out of it. Beethoven did that. Indeed, the entire first movement of Symphony No. 5 is two notes, and the first one was repeated twice. That kernel germinates over the next eight minutes into what can, over a few rounds of scotch, garner agreement as the greatest piece of music ever composed. By my count, in the history of west-world music there have been approximately, er, carry the one, hmnnnn, One Beethoven.

Spoiler: Chris Martin ain’t Beethoven. But in 2002 he did something Beethovenian.

The arpeggiated piano riff that formed the intro and instrumental chorus of what eventually became Clocks simply fell out of Chris’ head one night in an empty recording studio. He shared it with guitarist Jonny Buckland and they recorded a demo of it, intending to defer it to their third album as they were finishing their sophomore release A Rush of Blood to the Head. Band Manager Phil Harvey flatly insisted on including it in the current release, and so they re-recorded a finished version of the song, and the quarter-note rest is history. A number-one single in the New World, critical acclaim, samples for A-Listers (Brandy, Lupe Fiasco)… Clocks went off like a bomb, and Coldplay‘s legacy was cemented.

I’ve been weary – critical – of musicians who sing their riffs. It’s the musical equivalent of calling out your own name when you’re getting laid (hey, I didn’t bring golf into it, get off my case). But this was different. This was artful.

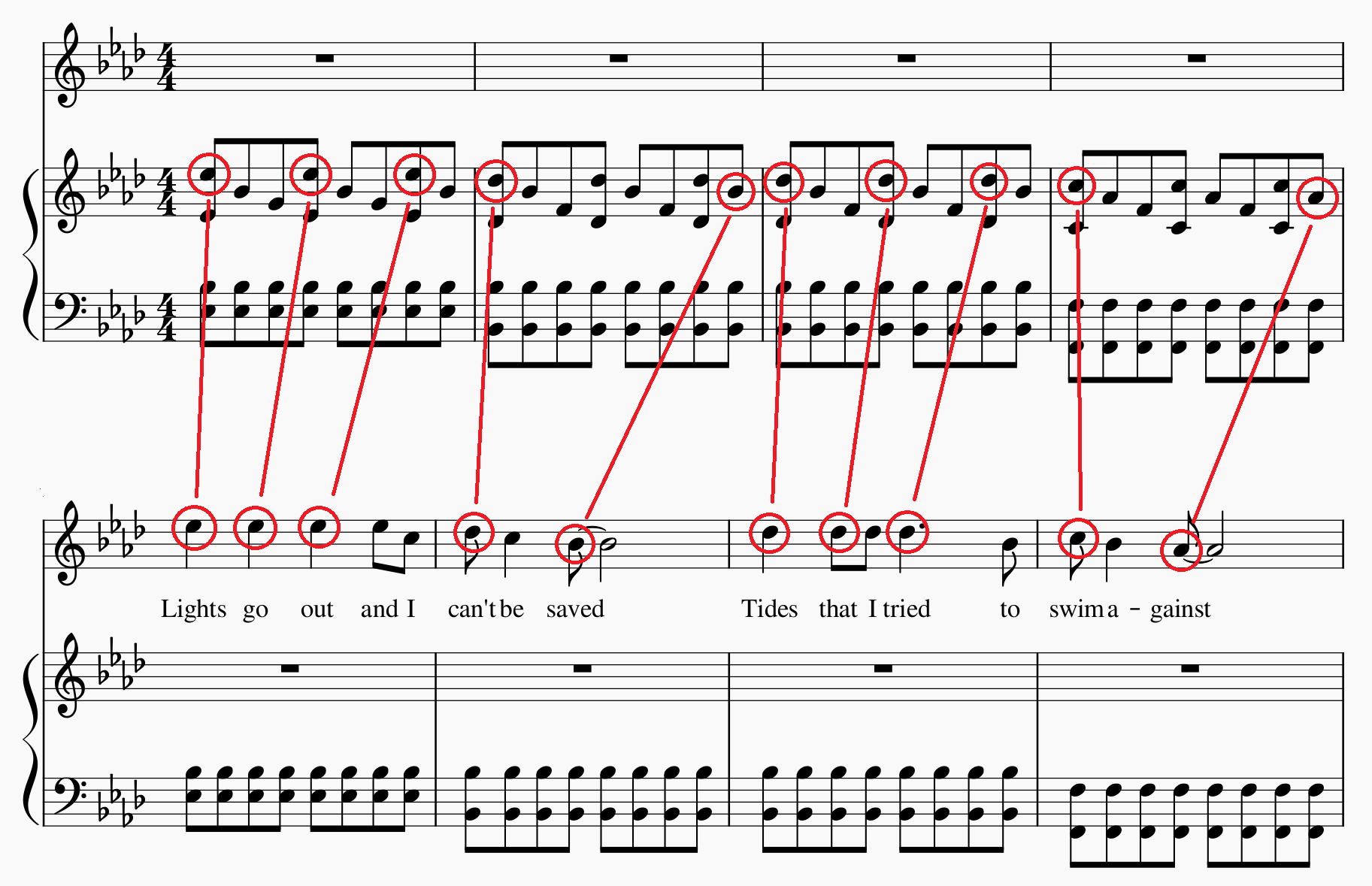

The piano hook is absolutely idiomatic to the keyboard, and not entirely singable. Go on, try to sing it. Hah. It’s just a downward arpeggio of three simple triads, in a rhythmic hemiola (Nerd Alert: if you want to impress your boozy friends, a hemiola is ‘twice three beats against thrice two beats’. Say it just like that, too). You could sing it if you have really good pitch and voice control, I suppose; it’s just not a naturally ‘vocal’ line. And remember, most of us can’t sing.

So what does Ludwig van Martin do? He just writes a vocal melody that takes the principal notes of the hook and shapes the melody with it. He simply takes the hookline, re-fabricates it into a shapely voice line, and sings it. And on top of that, we never hear the piano hook and his lyrical melody at the same time; they alternate throughout the song. The voice takes the verse, the hook takes the chorus.

[ed. Did you notice the key signature? A-flat major, right? Wrong!! Haha!! It’s actually in E-flat mixolydian. If you don’t know what that is or how to pronounce it, go to my reallyfuckingboring post on modes.]

Clocks isn’t just Songwriting; it’s Composition. Musical life grew here from the seed of an idea, and a pretty elemental one at that. It’s the kind of riff that any keyboardist could have played. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised that, in the course of mindless noodling, that same riff had been played countless times by equally countless players over the ages. It takes the spirit of a true artist to midwife something meaningful from it.