This is actually a two-part post. This one’s the geeky part.

I started it for any and all music lovers, but then realized that we need to understand a bit of music theory to get the full oomph.

So, non-musicians, we’re talkin’ here. Tired of hearing us tradespeople rambling on about major and minor and scales and triads and keys and tonalities? Don’t know which end of a piano to blow into? You’re in the right meeting.

Let’s demystify some of this and then mañana I’ll do the fun post. Whee.

Do this:

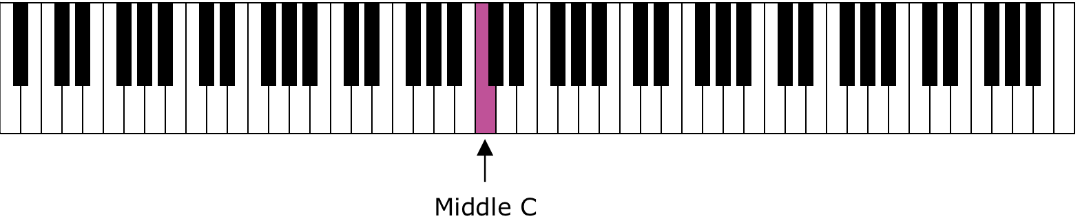

Next time you’re in front of a piano keyboard – OH, HERE’S ONE! – look at the white and black keys. Find Middle C

Now play each key, black and white, in ascending order (left to right) until the pattern of keys repeats (the next ‘C’ key before the couplet of black keys). You’ll have played 12 different notes.

Each of these adjacent keys you played, black and white, is said to be a ‘semitone’ apart (don’t sweat why it’s called ‘semi’, just smile and wave). Most of the time, white keys are a ‘wholetone’ (or, simply, ‘tone’) away from each other, because there’s a black key between them. Some white keys have no black key between them (B and C, E and F); and so they’re a semitone apart.

Good so far?

Okay, now play just the white keys in ascending order from that same Middle C, again until the pattern repeats. You’ll have played seven notes. Notice that some of the keys are a tone apart, some a semitone. Of course, that pattern of tones and semitones will change depending on which key you started on. If, for example you started on C (the first white key before the two-group of black keys), the pattern will be

T T ST T T T ST

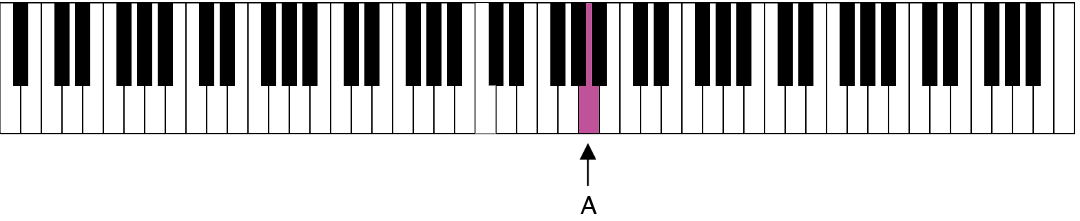

Then if you do the same thing but this time started on A (the white key between the second and third of the three-group of black keys)

Now the pattern of tones (T) and semitornes (ST) will be

T ST T T ST T T

These successions of notes that you’ve played are called ‘scales’. The first one had all twelve notes from one C to the next C, and so it’s called a ‘chromatic’ scale (12 consecutive semitones). The white-key scale you played starting o C had a certain pattern of tones and semitones that we call ‘Major’ and the second white-key scale you played starting on A had another, different pattern of tones and semitones that we call ‘Minor’. Major and Minor are also referred to as ‘modes’. Remember that.

Notice the different ‘feeling’ or ‘mood’ those two white-key patterns have? The Major mode is considered to be ‘brighter’ and ‘happier’ largely because the third note of the scale is a semitone higher than the third note of the minor mode, which is considered ‘darker’ or more melancholy. Why is that third note so special? We’re getting there, Jedi.

Still with me? Drink some alcohol. Good.

You might be wondering: if we start a white-key scale on some note other than C or A it would give us a different pattern of tones (T) and semitones (ST) from the ones we saw above. If we call a white-key scale that starts on C ‘major’ and a white-key scale that starts on A ‘minor’… what do we call the pattern of a white-key scale that starts on D? Or on F? Or on any of the other white keys?

That very question existed for musicians centuries ago when not all instruments could play all 12 notes of that first chromatic scale you played with the black and white keys above (horns and reed instruments, for example).

In those cases, if you wanted to change keys (to suit one’s voice range, for example), you were pretty much forced into using all those patterns of tones and semitones since there were no ‘black keys’ to adapt a pattern to every starting note.

So a song would start, end and emphasize (perhaps through a rhythmic downbeat) its principal note as the “home” note, or “root” or “tonic” of the piece. While one piece of music might focus on, say, the note G in its musical phrasing and focus, it was therefore said to be “in the key” of G. Another would repeat, emphasize, hover around and stick all its landings on D. So it’s in the key of D. The ‘mode’ – what we now call major or minor – was built in to the immutable pattern of tones and semitones for that particular note. D major therefore didn’t exist in most instrumental music because you simply couldn’t achieve the pattern above if you started a scale on D.

So, in effect, there were in theory seven modes, corresponding to the patterns that started on each of the ‘diatonic’ (ie, white-key) notes:

Starting on C: T T ST T T T ST (Ionian or in modern times, Major) Starting on D: T ST T T T ST T (Dorian) Starting on E: ST T T T ST T T (Phrygian) Starting on F: T T T ST T T ST (Lydian) Starting on G: T T ST T T ST T (Mixolydian) Starting on A: T ST T T ST T T (Aeolian, or in modern times, Minor) Starting on B: ST T T ST T T T (Locrian)

For reasons too lengthy to get into here, two modes have survived the natural selection process in the western world: Major (Ionian) and Minor (Aeolian).

Ah, what the hell, I’ll get into it.

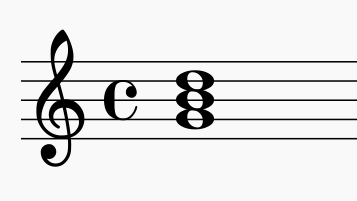

If you stack up three notes on top of each other on a staff line like this (here G, B and D, lowest to highest)

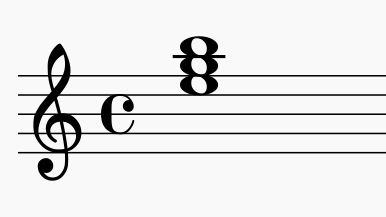

or this (here E, G and B)

it’s called a ‘triad’; schmancy name for a ‘chord’ of three notes; geeky term for multiple notes played at the same time.

A triad’s lowest note is the ‘root’ of the chord. The next note up is the ‘third’ (because it’s the third note up the scale from the root) and then the ‘fifth’ (because it’s the fifth note up the scale from the root). If the third is two tones up from the root, it’s a ‘major third’ and the whole of the triad or chord is said to be major; if the third is a tone plus a semitone up from the root, it’s a ‘minor third’ and the chord is said to be minor.

Because four of the above modes (Ionian, Lydian and Mixolydian) have a major third in its root-note triad, and three (Dorian, Phrygian, Aeolian and Locrian) have a minor third, musical tonality has conditioned our ears around two groups of modes, Major and Minor. Just out of practice, the Ionian and Aeolian modes have evolved as the ‘representatives’ of those two mode groups.

A triad’s ‘fifth’ (the third, top-most notes) is always three tones and a semitone above the root. With one ugly exception…

In the ‘Locrian’ mode, the fifth note is two tones and two semitones above the root. It makes for a jarring, dissonant sound, and that’s why the Locrian mode is never used – a chord built on its root note will never sound like a point of resolution, and so it will be difficult to convince the listener’s ear that a piece of music is in that key.

So what happened to the ‘other’ modes? Do any recording artists use them, ever?

That’s tomorrow’s post…